My plan was to write a single follow-up blog about upgrading my monitor, GPU, and processor. I made it most of the way through writing that post when I noticed that I was already over 3,000 words. I hadn’t even mentioned everything I felt I should mention, so I am going to split this update up into two or three posts.

I have a feeling this will be the shortest of the three blogs.

- My New Monitor: The Gigabyte G34WQC A Ultrawide at patshead.com

- Oh No! I Bought A GPU! The AMD RX 6700 XT

- My New Radeon 6700 XT — Two Months Later

- AMD Radeon vs. Nvidia RTX on Linux

- Putting a Ryzen 5700X in My B350-Plus Motherboard Was a Good Idea!

Why did I upgrade from two 2560x1440 IPS monitors to a single 3440x1440 monitor?

Does that even qualify as an upgrade? I was running a pair of QNIX QX2710 monitors at my desk since 2013. They were really cheap monitors, but they were quite nice! They looked good. I had them overclocked to 102 Hz for gaming. They were still working great!

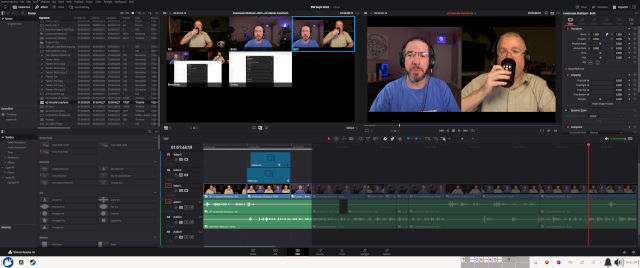

NOTE: I definitely won’t be winning any photo contests at r/battlestations. The green walls are ugly. The big soft-box light for podcasting, the permanent camera rig, and the microphone arm will always make my desk look cluttered no matter what I do!

The problem is that the QX2710 only has a single video input port, and it is a dual-link DVI port. I have been needing to replace my Nvidia GTX 970 for at least a year or two, and you can’t buy a modern GPU with DVI ports. The monitors were holding me back.

Having two 27” monitors on my desk made it challenging to find room for my podcasting camera. I was hoping I could make do with a single ultrawide monitor.

Why buy a VA monitor instead of an IPS? Why not a 38” ultrawide?

I talked about this a lot in the previous blog about the Gigabyte monitor, but I will summarize it again here.

The Gigabyte G34WQC A might be the best ultrawide gaming monitor under $400. It might even be the best choice under $500 or even $600. I am pretty sure I only saw a single IPS ultrawide gaming monitor under $700 while I was shopping, and it was an older model that topped out at 100 Hz.

There were a handful of ultrawide IPS gaming monitors starting at around $800, but I didn’t spend much time looking at them. If I am going to spend $800 on a single monitor, then I may as well spend $1,000 on a 38” 3840x1600 IPS ultrawide monitor.

So then why not spend $1,000 on one of those really nice 38” ultrawide monitors? I was a little concerned that this would be too big for full-screen gaming. I am not the least bit concerned about that after gaming on this 34” ultrawide for the last five weeks. I kind of wish I did buy a 38” ultrawide!

What I really want is a 38” ultrawide OLED display, but they don’t exist at this time.

- My New Monitor: The Gigabyte G34WQC A Ultrawide at patshead.com

Is an ultrawide too wide?

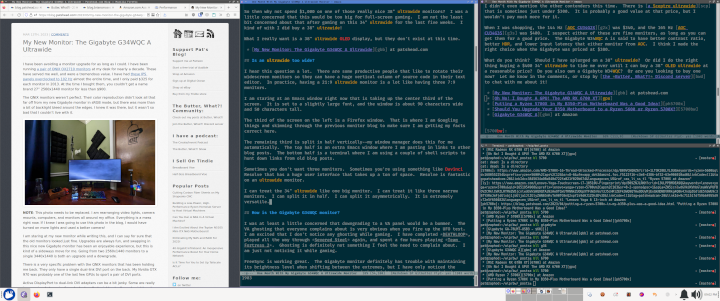

I hear this question a lot. There are some productive people that like to rotate their widescreen monitors so they can have a huge vertical column of source code in their text editor. In practice, having a 21:9 ultrawide monitor is a lot like having three 7:9 monitors.

I am staring at an Emacs window right now that is taking up the center third of the screen. It is set to a slightly large font, and the window is about 90 characters wide and 50 characters tall.

The third of the screen on the left is a Firefox window. That is where I am Googling things and skimming through the previous monitor blog to make sure I am getting my facts correct here.

The remaining third is split in half vertically—my window manager does this for me automatically. The top half is an extra Emacs window where I am pasting in links to other blog posts. The bottom half is a terminal where I am using a couple of shell scripts to hunt down links from old blog posts.

Sometimes you don’t want three monitors. Sometimes you’re using something like Davinci Resolve that has a huge user interface that takes up a ton of space. Resolve is fantastic on an ultrawide monitor.

I can treat the 34” ultrawide like one big monitor. I can treat it like three narrow monitors. I can split it in half. I can split it asymmetrically. It is extremely versatile.

How is the Gigabyte G34WQC monitor?

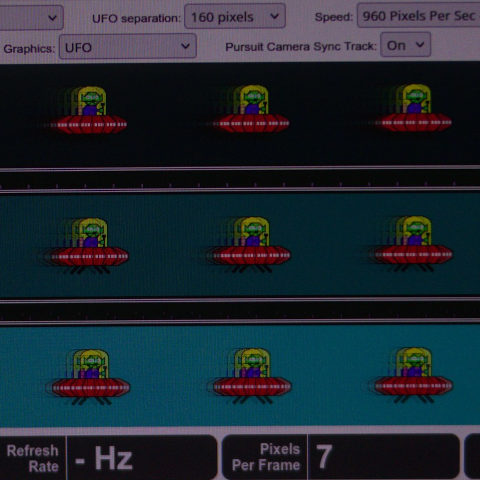

I was at least a little concerned that downgrading to a VA panel would be a bummer. The VA ghosting that everyone complains about is extremely obvious when you fire up the UFO test. I am excited that I don’t notice any ghosting while gaming. I have completed DEATHLOOP, played all the way through Severed Steel again, and spent a few hours playing Team Fortress 2. Ghosting is definitely not something I feel the need to complain about. I am just not noticing it while gaming.

FreeSync is working great. The Gigabyte monitor definitely has trouble with maintaining its brightness level when shifting between the extremes, but I have only noticed the problem on loading screens. I have not noticed the brightness shifting around during gameplay.

There are some good things you can say about the Gigabyte G34WQC that I can’t test. I read that it has just about the best input latency and response time you can get from an ultrawide 3440x1440 in this price range. It is also supposed to have better color accuracy and more dynamic range than other HDR gaming monitors in the same price range.

It looks pretty good to me, but I have no equipment for testing any of that. I do feel like I made a good choice. This is almost definitely the best monitor for what I do that costs less than $400.

The cheapest IPS ultrawide gaming monitors start a few hundred dollars higher, and the more modern offerings with better specs cost even more than that. It is really easy to dismiss all the monitors between my 34” Gigabyte monitor and one of the amazing 38” ultrawide monitors that regularly go on sale for around $1,000.

I kind of wish I splurged on a 38” ultrawide 3840x1600 IPS gaming monitor, but I am also quite pleased that I saved $630. Those were the only two choices I had. I didn’t like any of the rungs on the pricing ladder between the two!

- My New Monitor: The Gigabyte G34WQC A Ultrawide at patshead.com

Is 144 Hz enough?!

I am certain that shaving off every millisecond of latency possible will be a help to someone. Anything that helps you pull the trigger before your opponent can in a multiplayer game gives you an advantage. These advantages keep getting smaller and smaller, but they are there.

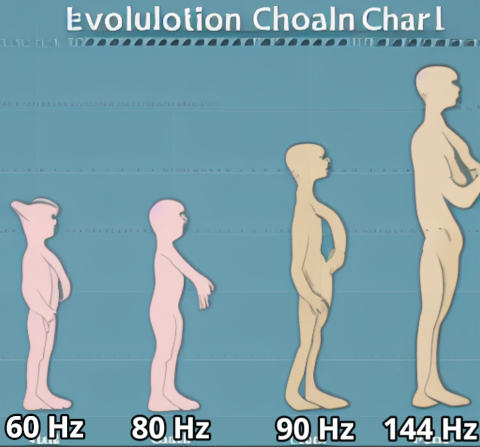

I definitely don’t want to say that I would do a good job picking out the difference between Team Fortress 2 running at my old monitor’s 102 Hz and my new monitor’s 144 Hz. I have no confidence that I could tell the difference with any degree of confidence. I would have no trouble picking out 60 Hz.

While I was farting around with Borderlands 3 settings, I did figure out roughly how many frames I need to be pleased with a first-person shooter. Anything under 80 Hz feels very much like 60 Hz, and it just doesn’t seem smooth. Anything over 90 Hz feels pretty good, and I am not certain that I could tell the difference between 110 Hz and 144 Hz.

There is probably a missing link on the evolutionary chart between 80 Hz and 90 Hz where things start to feel much better than 60 Hz, but I didn’t try hard to find it!

Is VA really OK?!

Here’s what I think I know. All VA panels should have better contrast ratios than most or possibly all IPS panels.

All VA panels have ghosting issues. That is where you can see a fading ghost of the previous image a few frames after it has already moved. Some are worse than others.

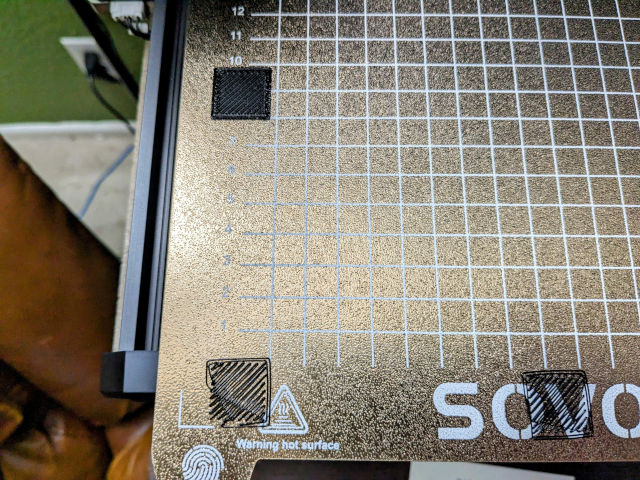

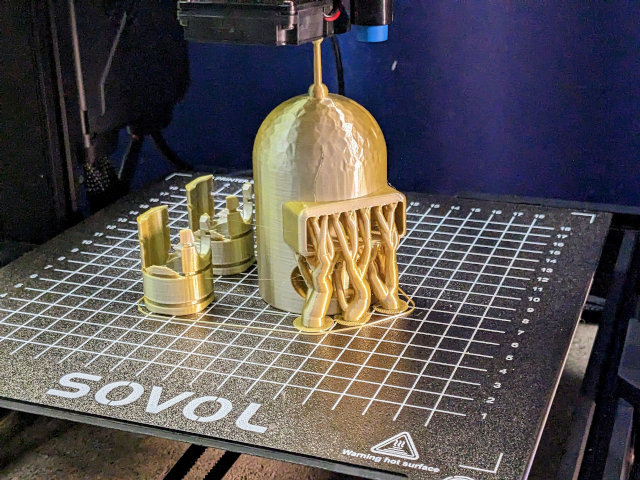

I know for certain that there is at least some ghosting on my Gigabyte G34WQC. I can see it in the UFO test.

NOTE: This photo was taken at 1/2000 second shutter speed. Bright cyan to black or bright yellow is probably about as awful as you can possibly make the ghosting look. You can definitely see a couple of frames of ghosting with your naked eye, but nothing looks even remotely this bad for me while actually gaming.

I also know that some VA panels have really horrible ghosting, while others handle it pretty well. I suspect that my Gigabyte handles ghosting pretty well. I have not noticed it while playing any games so far.

I am also under the impression that VA panels have more ghosting at higher brightness levels, and IPS panels can usually reach much higher levels of brightness. I have total control of the lighting in my workspace. I don’t need my monitor to reach brightness levels to compete with sunlight.

The Gigabyte G34WQC’s maximum brightness is only 350 nits, and I run it with the brightness set to 40%. My 14” 2-in-1 Asus laptop has a rather dim IPS display that can only manage 250 nits, and I run it at about 35% brightness in my office.

I don’t know if the Gigabyte G34WQC would be as nice if you have to crank it up to the maximum just to see it in your bright environment, but it is quite good in my moderately lit home office.

Conclusion

I didn’t even mention the other contenders this time. There is a Sceptre ultrawide that is sometimes just under $300. It is probably a good value at that price, but I wouldn’t pay much more for it.

When I was shopping, the 144 Hz AOC CU34G2X was $340, and the 165 Hz AOC CU34G3S was $400. I suspect either of these are fine monitors, as long as you can get them for a good price. The Gigabyte W34WQC A is said to have better contrast ratio, better HDR, and lower input latency that either monitor from AOC. I think I made the right choice when the Gigabyte was priced at $380.

What do you think? Should I have splurged on a 38” ultrawide? Or did I do the right thing buying a $400 34” ultrawide to tide me over until I can buy a 38” OLED ultrawide at a reasonable price? Do you also own a Gigabyte W34WQC? Or are you looking to buy one now? Let me know in the comments, or stop by the Butter, What?! Discord server to chat with me about it!

- My New Monitor: The Gigabyte G34WQC A Ultrawide at patshead.com

- My New Radeon 6700 XT — Two Months Later

- Oh No! I Bought A GPU! The AMD RX 6700 XT

- AMD Radeon vs. Nvidia RTX on Linux

- Putting a Ryzen 5700X in My B350-Plus Motherboard Was a Good Idea!

- Should You Upgrade Your B350 Motherboard to a Ryzen 5600 or Ryzen 5700X?

- Gigabyte G34WQC A at Amazon